1. Introduction

I began assembling maps about the Copper River after finding a collection

of historical Alaska maps on the website of the geological survey of

Alabama. The maps came from a variety of

sources and time periods. As I added

more maps to the collection I began to ask myself what do these maps tell us

about the history of Alaska? At first it

seemed fairly straightforward, the maps showed the accumulation of geographical

knowledge and the development of the Copper River. Explorers, prospectors, geologists,

anthropologists, and biologists developed maps for their own purposes adding

layers of knowledge. But then I ran across

essays on critical cartography and phrases such as “cartographic dispossession”

defined as when Euro-Americans diminished and delegitimized the territorial

claims of indigenous inhabitants through map making (Hämäläinen 2008:

195). This series of maps[1] illustrates

how the upper Copper River was colonized through cartography. They are the ideal text for showing how Indian

land was transformed into EruoAmerican territory.

Nation states acquire power by creating physical boundaries through the process of mapping, measuring, and surveying, a classificatory exercise that enhances control over a profitable hinterland, such as interior Alaska (Innis 1950; Cruikshank 2005). These efforts are rationalized as both a production of knowledge and serving the interests of state administration but they undermine local traditions –so, for example, Native toponyms are lost. In the process landscape is transformed, provided new names reflecting an alien, imposed history, and culture.

Nation states acquire power by creating physical boundaries through the process of mapping, measuring, and surveying, a classificatory exercise that enhances control over a profitable hinterland, such as interior Alaska (Innis 1950; Cruikshank 2005). These efforts are rationalized as both a production of knowledge and serving the interests of state administration but they undermine local traditions –so, for example, Native toponyms are lost. In the process landscape is transformed, provided new names reflecting an alien, imposed history, and culture.

Initially explorers and cartographers relied on Native knowledge in

producing the first maps and frequently retained Native toponyms to fill in the

blank spaces. Native knowledge was

instrumental in development of both the fur trade and the mining industry as

Natives revealed the location of trails and later deposits of copper and gold. But as colonialism advanced and

administration became the priority, the Native presence gradually disappeared

under an overlay of alien place names.

In the colonizing process maps serve as ideological tools in making

claims about a particular territory.

Maps preceded people and then assumed a normative role in

pre-establishing a spatial order for hegemonic claims. Place names are one tool used in both

establishing and securing those claims.

Toponyms can be read as the inscribed body of the nation, as glosses on

a somewhat magical unit “The United States of America,” (Boelhower 1988). Through a deliberate process of inclusion and

exclusion American cartographers transformed Alaska and the upper Copper River

into American territory. The new place

names reflected an American history and culture that marginalized and

eventually disappeared the original inhabitants.

Maps are assumed to be reality but are only an explanation or interpretation

of reality. We assume they reflect reality

in part because they are produced through scientific means and use conventions

such as north, south, east and west that we think natural, i.e. exist in nature.

But as the linguist Jim Kari has shown, Ahtna geography is based on a set of

principle different

from those used by western cartographers.

For one thing Northern

Dene do not make use of the four cardinal directions for orientation, and terms

for left and right are not used at all for spatial orientation or in geographic

terminology (Kari 2011). All directions

are anchored toward the major river in the drainage. For most Ahtna this is the Copper River but

for the Western Ahtna it is the Susitna River.

In addition, Ahtna geographic terms

are much more precise than the standard U. S. G. S. feature types. For example, the Ahtna have words describing not only the flow INTO lake (‘ediłeni),

but the flow FROM lake (‘edadiniłeni)

and the flow from a HILL SIDE (ts’idiniłeni).

For

over a millennium the Ahtna have inhabited the Copper River Basin. Traditional Ahtna territory encompasses

35,000 square miles including the entire Copper River Basin and parts of the

upper Susitna River drainage (Figure 1 below).

Lt. Allen estimated Ahtna territory to

be 25,000 square miles (Allen 1887:128), but he probably knew nothing of the

Western Ahtna.

| Figure 1. Ahtna Traditional Territory, from Kari. |

The

linguist James Kari has documented over 2,500 Ahtna place names. Today about 237, or about 10 percent, of the over 2000 officially recognized toponyms

for the Copper River derive from an Ahtna place name (Kari 2008). Approximately 125 of those names were mapped

or written down prior to 1910 (primarily by Lt. Allen and Geologists of the

U.S. Geological Survey), while another 100 names were added later (Kari 2008). These names only dimly reflect the Ahtna

presence in the Copper River and in no way indicate that the Copper River is

the Ahtna homeland occupied for at least a millennium.

The

name Ahtna designates both a group of people and their language. The Lower Ahtna are one of four groups of

Ahtna who inhabit the Copper River Basin, the others are the Middle, Western,

and Upper Ahtna. Each group speaks a

dialect of the Ahtna language.

The

concept of territoriality is firmly established in Ahtna ideology. Non-Native explorers traveling in the Copper

Basin at the end of the 19th century saw the strength of territorial

boundaries, noting that the Ahtna had

by

common consent or conquest, divided the valley into geographical

districts. Each band keeps to its own

territory while hunting and fishing, and resents any intrusion on the part of a

neighboring band (Abercrombie 1900).

Territorial rights were validated by continuous use but intermarriage carried obligations to share access to harvest areas so that members of several bands often had access rights to a particular territory. Territories included a variety of subsistence resources that could be exploited as those resources became available in the different seasons of the year (Reckord 1983).

Figure 2 (below) shows the density of historical Ahtna fishing sites along

the Copper River and tributaries. The

map also shows contemporary community and historic communities that had

inherited chief’s titles.

| Figure 2. Historical Ahtna Salmon Fishing Sites along the Copper River and Tributaries. |

Traditional Ahtna leadership was

complex and multidimensional and at the highest level closely tied to the

land. In the Ahtna language there is no

word that translates as chief. A leader

who controlled a large territory was called Nen’ke

hwdenae’ literally “on the land person.”

These men held inherited titles that were a combination of a place name

and the title ghaxa or denen so, for example, the chief of

Mentasta was known as Mendaes Ghaxen

‘Person of Shallows Lake’ (No. 84 on Figure 2), while the headman at Taral was

known as Taghael Denen (No. 3 on Figure

2). Ghaxa indicated that the man who held the title was a “rich man”

who controlled that village and the surrounding area (Kari 1986:15; Kari

1990:150).

2. The Fur Trade

The Wrangell map of 1839 (Figure 3, below) is probably

the earliest map of the Copper and Susitna rivers, encompassing all of Ahtna

traditional territory. It demonstrates the

stage in the cartographic process that relied exclusively on Native

information. At the time the map was

produced the Russian American Company was attempting to extend its influence

into interior Alaska. Ferdinand von

Wrangell, chief manager of the Russian American Company, compiled information from

sketch maps, a diary made by the Russian explorer Klimovskii, (who explored the

River in 1819 and named Mt. Wrangell) and information received from Dena’ina,

and Ahtna informants (Wrangell 1980 [1839]). Analysis

of toponyms by Kari (1986) concluded that Dena’ina Athabaskans from Cook Inlet provided

much of the information. For example the

Upper Ahtna village of Batzulnetas, written as “Nutatlgat” is based on the

Dena’ina pronunciation ‘Nutł Kaq’, and not the Ahtna, which is Nataeł Caegge

(‘Roasted Salmon Place’). Kari also

concluded that the Dena’ina may have deliberately provided misinformation to

the Russians because the trail leading from Copper River to Athabaskan (“Kohlschanen”) villages passes near Mt.

Wrangell (“vulkan” on the map) is almost a mirror-image of the actual trail around the base of

Mounts Sanford and Drum (Kari 1986:105).

| Figure 3. Wrangell Map of 1839. |

According to Ahtna elder Andy Brown the trail

went around the base of Mt. Sanford and Mt. Drum, crossed over the upper Nadina

and Dadina rivers, the Chestaslina River, and ran into the upper Kotsina drainage

before heading across the Chitina River to Taral (Kari 1986). The trail was eventually co-opted by the

Americans and became known at the Millard Trail. According to Wilson Justin of Chistochina this

trail belonged to the Ałts’e’tnaey

and Nal’cine clans.

Wrangell’s map illustrates the

limits of Russian hegemony. The single

feature alluding to a Russian presence is “Kupfer Fort” located just north of

the mouth of the Chitina River. Kari

(2008) speculates that Kuper Fort may also refer to the settlement Tsedi Kulaenden (“where copper exists”),

which had an inherited chief’s title Tsedi

Kulaen Denen “Person of Copper Place.

The map also illustrates that in

1839 the Ahtna were very much in control of their traditional territory, which

included the entire Copper River Basin as well as portions of the upper Susitna

River drainage. According to Wrangell

the “Galtsan” or Tanana river people traveled ten days to Lake Knitiben to hunt

“reindeer” (i.e. caribou), and that the Dena’ina traveled to this lake to trade

with the Tanana. He goes on to say that

Upper Ahtna from the village of Nataełde, and Ahtna from Tazlina Lake (identified

as Mantilbana on the map) traveled to Lake Chulben to trade with the Dena’ina

and hunt caribou (Wrangell 1980 [1839]).

Figure

4 is a map of British North America. By

1854 the British claimed most of Northern North America including portions of Alaska,

but they had little first hand knowledge of the Copper River, which remained firmly in the hands of the Ahtna. Information about the Copper River on

this map seems to have been derived largely from the Wrangell Map with only

slight changes such as the addition of Wrangel Vol. (sic), and the elimination

of the Ahtna trail around Mt. Wrangell. Nataeł Caegge (written as “Natalgat”), “Lake

Knituban” and Mantilbana L. all appear on this map as does the Russian trading

post which is now labeled “Copper Ft.”

In 1867 Russia sold

Alaska to the United States. Russia laid

legal claim to Alaska through the rule of discovery which was an agreement

between European nations that the nation which first discovered a land in the

new world acquired title to the land and dominion over the original inhabitants

(Case 1978:48). Russia therefore had a

legal right, in European terms, to sell Alaska and the United States the right

to purchase it. The 1867 treaty has been

referred to a quitclaim whereby the U.S. acquired whatever dominion Russia had

possessed immediately prior to cession (ibid:56).

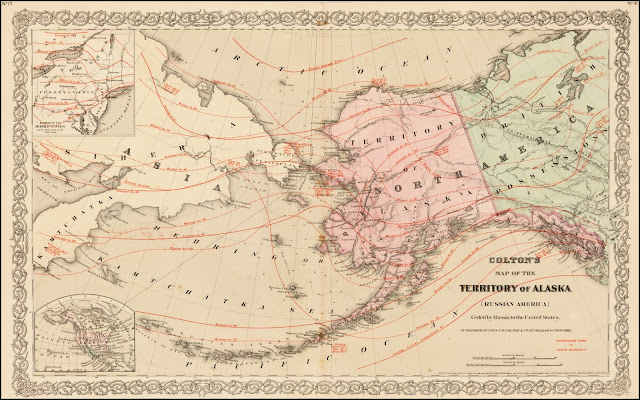

| Figure 5. Colton's Map of the Territory of Alaska, 1867. |

Reactions to the purchase were mixed, some calling it Seward’s Folly

while other praised it for weakening British claims to Northwest America. The historian E. P. Oberholtzer summarized

the opposition commenting on the current problems the United States was having

governing aboriginal people in the present boundaries of the republic. He asked, “Could it be that we would now,

with open eyes, seek to add to difficulties by increasing the number of such

peoples under out current national care?”

Oberholtzer also questioned what resources were available expect for

furs, which he thought had already been hunted to near extinction (Wikipedia

“Alaska Purchase,” May 19, 2015).

Initially the public and the government ignored the new territory. Little exploration took place. Cartographers gained detailed knowledge of

the Alaskan coast and some basic knowledge of interior Alaska but information

about the Copper River remained scarce as it was during the Russian period. On Colton’s map (Figure 5) of the territory produced in

1867 all of the Native toponyms along the Copper River have disappeared. The inset below shows the “Atna or Copper

River,” Mt. Wrangel, and Mantilbana L. along with the now long abandoned

Russian trading post referred to as “Odinotenka,” but little else.

Colonial powers acquired new territory in order to obtain land and

resources. To make use of these new

assets they had to be systematically located, inventoried, and mapped. Often these new lands were already inhabited

so the current residents had to be inventoried as well. William H. Dall compiled the information on Figure

6 (Below) showing the distribution of Native tribes in Alaska and western Canada. Dall was a member of the Western Union

Telegraph Expedition in 1865. In 1871,

he was appointed to the United States Coastal Survey, and later joined the U.S.

Geological Survey as a paleontologist.

Dall was part of the American effort to inventory the mineral, animal,

and human resources of the new territory.

In some ways this map resembles later maps produced by geologist with

swirls of color indicating the location of different Native peoples and the

languages they spoke. The spelling Ah-tena

was introduced by Dall who erred in thinking this was “their own name for

themselves” (Goddard 1981). The map is

important because it demonstrates and acknowledges the Ahtna presence in a

large swath of territory that includes the entire Copper River Basin.

|

“Map Showing the Distribution of Natives Tribe of

Alaska and Adjoining Territories,” 1875.

|

3. Lt. Henry Allen and American Exploration

of

the Copper River

In 1885 the Indian wars were

coming to an end and the veteran Indian fighter Nelson A. Miles was put in charge

of the Army’s operations in the Pacific Northwest. Miles was fascinated with reports from Alaska

and in 1883 sent Lt. Frederick Schwatka on an expedition to explore the Yukon

River. Schwatka’s success led Miles to

determine a more ambitious goal, to ascend the Copper River and cross the

Alaska Range into the Yukon River drainage.

A new cartographic period for the Copper River was about to begin.

In the spring of 1884 General

Miles sent Lt. William Abercrombie to explore the Copper River but Abercrombie

turned back after advancing only fifty miles.

So in the spring of 1885 Allen and two hand picked men, Sergeant Cady

Robertson and Private Frederick W. Fickett began their expedition. Two prospectors also joined the expedition,

John Bremner and Pete Johnson. In the

spring and summer of 1885 Allen managed to travel 1,500 miles, ascending the

Copper River, cross the Alaska Range, floating down the Tanana River to the

Yukon, then crossing overland from the Yukon to Koyukuk River, floating down

that river to the Yukon and then out to St. Michael on the Bering Sea

coast. The goal was to explore uncharted

territory and report on the disposition of the Native people, including whether

they posed a threat to future development of the territory. The Ahtna, whose territory included all of

the upper Copper River drainage, had a fierce reputation and memories of

ill-fated Russian expeditions lingered.

Born in Kentucky in 1859, Allen

attended West Point, and served in the army for 41 years, including as commander

of the American Occupation Forces in Europe between 1919 and 1923. He was educated in languages, could read both

French and German, and was trying to learn Russian so he could read the Russian

literature on the Copper River (Twichell 1974).

Allen’s interest in languages is reflected in the fact that he compiled a

brief word-list of the Ahtna language and recorded and retained Ahtna toponyms

for some of the major tributaries of the Copper River.

Allen’s exploration, was

significant because it 1) provide the first detailed information about the

geography of the Copper, Tanana, and Koyukuk rivers; 2) proved that it was

possible to travel between the Copper and Tanana rivers; and 3) showed that if

explorers followed local protocols and were respectful travel was safe. As he traveled along the Copper River, Allen

named many geographic features, including most of the river’s major

tributaries, and the major peaks of the Wrangell Mountains. All of these names are in use today.

Allen produced several maps from

his explorations. Figure 7 is the map

Allen made soon after his return. The

Cartouche, in the upper left hand corner, reads:

ALASKA

North of the 60th Parallel Showing the Exploration of the

Party Commanded by

Lieut. H.T. Allen 21th U.S. Cavalry.

Drawn by Lieut. Allen, J.H. Colwell, and Paul Eaton

in the Adjutant General’s Office, Washington.

“The greater part of the Copper, Tanana and

Koyukuk Rivers is included in the discoveries of the party. Chart No. 960 U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey,

1884 has otherwise been followed except as to most of the Yukon River which is

from the charts of Capt. Raymond and Lieut. Schwatka, U.S.A. and the Unnalakik

River which is from the field notes of the party.”

| Figure 7. Allen’s Map of Alaska |

COPPER AND CHITTYNA RIVERS

ALASKA.

From the Explorations of Party

Commanded By

Lieut. H.T. Allen 21 U.S. Cavalry

| Figure 8. Allen’s published map of the Copper and Chitina Rivers, 1887. |

There are obvious differences

between these two maps. First, Figure 7

includes all of Alaska while Figure 8 shows only the Copper and Chitina rivers. Second, Figure 7 has some additional

information about the upper Copper River not included in Figure 8. The Chisana River is labeled in Figure 7 but

there is no label for the Nabesna River and the White River is shown as “Natisna,”

the Native name Allen learned while he was at Batzulnetas. Another interesting feature is the trail Allen

labeled “Sereberinikoff 1848” indicating a route from the Matanuska River and

down the Tazlina River taken by the Russian explorer in 1848 before his party

was killed by Ahtna (see Kari 1986).

Several Ahtna guides attended

Allen on his trip up the Copper River and he was made well aware of territorial

boundaries, observing that different leaders controlled various segments of the

Copper River. Nicolai was the “autocrat”

of the Chitina River and Taral, while Conaquánta and Liebigstag “held sway”

over the river between Taral and the mouth of the Tazlina. Batzulnetas was the leader of the Tatlatans –

or Ahtna who lived on the upper Copper River.

According to Ahtna elder Andy Brown (quoted in Reckord 1983b:77) Chief

Nicolai told Allen, "We have law in our village that you can't stay here.

You've got to get your own place to stay. We got law here and it's the same all the way

up the river." Nicolai then said he

would send a man so that nothing happened to Allen and the guide would tell

other Ahtna, …"They not Russians. Americans

look like good people to us. Don't

bother them." Then from the next

chief other guides would be sent further up the river so that Nicolai's men

could return home.

Allen remarked at “how great is

the geographical knowledge of these primitive people.” The guides knew the names of all the streams

flowing into the Copper River, many of which Allen recorded. Over time these names have become altered so that Kentsii Na’, (“spruce bark canoe river”) became the Tonsina River, Tl’atina’ (“rear water”) became the Klutina

River, Tezdlen Na’ (“swift current

river”) became the Tazlina River, C’el

C’ena’ (“tearing river”) became the Gulkana River, and Ggax Kuna’ (“rabbit river) became the Gakona River. Note that in the Ahtna language Na’, such as

in Tezdlen Na’, is the word for river.

In addition to collecting Ahtna

place names for rivers, Allen recorded the names of Ahtna leaders he met along

the way. Instead of using the

appropriate Ahtna place name, Allen often substituted the name of the leader

and for a number of years these names appeared on subsequent maps of the Copper

River (see below). The Ahtna call “Liebestag’s

village,” Bes Cene, or “base of river

bank” (No. 26 on Figure 2), while “Conaquánta’s village” is probably Nic’akuni’aaden, or “place that extends

off from shore” (No. 35 on Figure 2).

Perhaps the most famous of these substitutions was Batzulnetas. This settlement is located at the confluence of Tanada Creek and the

Copper River, and in the Ahtna language is called Nataeł Caegge or “Roasted Salmon Place” (No. 89 on Figure 2). On the Wrangell map of 1839 Nataeł

Caegge is labeled “Nutatlgat” a Russianized translation for the

Ahtna place name. Allen called Nataeł Caegge Batzulnetas, using the name

of the leader/shaman Bets’ulnii Ta’ “Father

of someone Respects Him” who was actually the headman for the village at the

mouth of the Slana River (Kari 1986).

The name Batzulnetas stuck and is often used by Native people today, and

it appeared on many subsequent maps of the river.

While Allen used Ahtna place

names for the major tributaries of the Copper River he named the mountains,

certainly the most prominent features of the basin, after obscure Americans who

have no connection to Alaska or the Copper River. In the Copper Basin the most dominant

geographic feature is the great phalanx of the Wrangell Mountains, named after

a Russian, as is the enormous shield volcano Mt.Wrangell (14,163

feet). Allen named Blackburn (16,390

feet), Sanford (16,337 feet), and Drum (12,010). In the Ahtna language the Wrangell Mountains

are called K’ełt aeni, a word of

ambiguous meaning that can be loosely translated as “one who controls the

weather.” Mt. Wrangell is called K’ełt aeni, but also Uk’ełedi “the one with smoke on

it.” Mt. Drum is referred to as Hwdaandi K’ełt’aeni or “downriver K’ełt’aeni,” while Mt. Sanford is Hwniindi K’ełt’aeni or “upriver K’ełt’aeni. Mt. Blackburn is K’a’si Tlaadi “the one at cold headwaters.”

4. Gold Rush: The Klondike Stampede of 1898

In 1898 gold was discovered on

the Klondike River in what is now the Yukon Territory of Canada. One result was a stampede that brought

thousands of people to Alaska. The

problem was access, how to reach the gold fields? Initially the stampeders followed a trail

over the Chilkoot Pass and down the Yukon River. But Americans wanted an all American route

that did not go through Canada. One

route led over the Valdez glacier to Klutina Lake and then up the Copper River

and through Mentasta Pass to the Tanana and Yukon rivers. Maps were produced to guide stampeders who

chose to follow the Copper River route to the gold fields. The maps below are examples produced for the

gold rush.

Figure 9 (black map below), is a map by the Canadian

geologist and cartographer J.B. Tyrrell, titled “Copper River Alaska Route

Map.” It is a traveler’s guide to the

Copper River. All of the toponyms

collected by Allen appear on this map along with bits of additional information

from the 1891 expedition of C.W. Hayes and F. Schwatka. In 1891 Hayes and Schwatka ascended the White

River and entered the Copper River basin via Skolai Pass traveling down the

Chitina River to the Copper. Like Allen,

Hayes recorded and retained Native place names sometimes slightly modifying

them for easier pronunciation (Hayes 1892).

Hayes was also creative with names, for example naming the pass between

the White and Copper rivers “Skolai,” which he said was the Native

pronunciation for the name Nicolai. In

Ahtna the pass is called Nadzax Na’Tates

referring to the passage into the White River (Nadzax Na’ or “murky river”).

|

|

In the right had corner of his map Tyrrell lists “Distances

from Alaganik” including the distances to specific villages such as Liebigstag

and Conagunto (sic). He also included

information on river conditions, locations for forage for horses, and hearsay

evidence on the presence of gold, copper, and iron. There is a note about where to find “Game

etc.” giving the impression that it would be easy to live off the land when in

fact Allen nearly starved to death. He

also quotes Haye’s comment about the Ahtna”

The Copper River Indians have an unenviable reputation for

treachery and hostility to whites; but we saw nothing to justify it. They are greatly superior to the Yukon

Natives physically, and have much more elaborate family and tribal

organization.

While Tyrrell’s map acknowledges the presence of the

Ahtna there is no question that the Copper River is American territory. There is no indication that the Copper River

basin is Ahtna territory or that people should request permission to cross

Ahtna land or use the resources found on that land. This message is even more evident from Figure

10 (white map below), Abercrombie’s map “showing a proposed U.S. govt. mail road and shortest

feasible all American Railroad route from Port Valdez via Copper Center....” As this map implies there is absolutely no

doubt that Americans have the right to build a road and railroad right through Ahtna territory, even using a

traditional trail controlled by an Ahtna clan (labeled the Millard trail).

|

| Figure 10. Abercrombie's map of the Copper River, 1898. |

American explorer’s, including Abercrombie, were well aware

that the Ahtna claimed the Copper River and had defended those claims with

violence. More than once Americans noted

territorial boundaries and they had encountered resistance when they did not

ask permission to use the local resources.

The prospector W. Treloar told of an encounter with an Ahtna kaskae from Mentasta:

There was an Indian village a short

ways above us and they had traps in the stream but were not catching many fish

and when they saw us catching them it did not set very well with them. The old chief came down and stormed around

and talked Indian to us.

The chief then sent

…another Indian came down, one who had been out to Fortymile

Post and could speak a little English.

He told us chief heap mad he say P-hat man (meaning white man) must not

catch fish or else P-hat man leave quick.

P-hat man catch all fish Indian man all die, so to pacify him we sent

him a lot of fish. Before long the chief

came down to our camp again and shook hands with us then he took up a fish and

ran his hands across the back of its head and motioned that he wanted the

head. Then he gave us to understand we

could catch fish but we must give him the heads. We assented to this and he went away pleased.

When the United States acquired the Territory of

Alaska from Russia, the treaty conveyed to the United States dominion over the

territory, and title to all public lands and vacant lands that were not

individual property. Land claimed and

used by the Ahtna, who were classified as 'uncivilized' tribes in the treaty,

were not regarded as individual property, and the treaty provided that those

tribes would be subject to such laws and regulations as the United States might

later adopt with respect to aboriginal tribes.

In other words, traditional Ahtna territory became part of the “public

domain" until Congress acted otherwise. Congress did, through various laws attempt to

protect the Alaska natives in their "use or occupation," and in 1884

passed the Alaska Organic Act. Section 8

of the Act declared that:

.

. . the Indians or other persons in said district shall not be disturbed in the

possession of any lands actually in their use or occupation or now claimed by

them but the terms under which such persons may acquire title to such lands is

reserved for future legislation by Congress.

But

this Act did not constitute recognition of aboriginal title and these maps

recognize the legal claim of the United States over Ahtna traditional territory

in spite of the Ahtna’s own assertion that the Copper River was their territory

(Information for this section comes from akhistorycourse.org Governing Alaska:

Native Citizenship and Land Issues and Richard S. Jones. “Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971

(public Law 92-203): History and Analysis together with subsequent amendments.

Alaskaool.org. Accessed 6/3/2015.)

5. Development: Roads, Telegraph lines, Copper,

and Fisheries

The desire for an all American

route to the Klondike resulted in the U.S. Army constructing a pack-trail

between Valdez and Eagle in 1898. The

project became known as the Trans-Alaska Military Road and was consistently

upgraded and eventually renamed the Richardson Highway. After a visit by the U.S. Senate committee on

territories in 1903, congress recommended that the war department construct a

trail system and upgrade the Valdez-Eagle wagon road. Congress then approved legislation

establishing a commission to oversee these and other improvements in January of

1905. The Board of Road Commissioners of

Alaska more commonly known as the Alaska Road Commission or ARC was formed in

1905 as a board of the U.S. War Department.

Figure 11 is one of four sheets published in 1909 by the Alaska Road

Commission showing trails and roads in Alaska.

This sheet shows routes leading into and out of the Copper Basin.

Congress also authorized construction of

telegraph line between Valdez and Eagle and by 1904 the Alaska Communications

System (ACS) had stretched a cable and established “meteorological stations”

between Valdez and Eagle. Figure 12 shows the route of the

telegraph line strung between Valdez and Eagle and the Telegraph stations.

|

|

|

|

In the EuroAmerican imagination the upper Copper River is famous for two things: copper and salmon. Copper can be found lying on the ground throughout certain parts of the upper Copper River drainage and the Chitina Basin has particularly rich deposits located within a 120 km arch stretching between the Kotsina and Chitistone rivers (Mendenhall and Schrader 1903:16; Moffit and Maddern 1909:47). Archaeologists think the Ahtna began using copper between 1,000 and 500 years ago producing arrowheads, awls, beads, personal adornment, knife blades, and copper wire probably through a process of heating and pounding or cold hammering (Workman 1977; Cooper 2012). Copper was also widely traded throughout eastern Alaska so it is not surprising that Europeans learned of the region’s copper deposits early on in their contact with the Ahtna. The first written reference to the Ahtna and to copper comes from a report describing a Russian expedition to the mouth of the Copper River in 1783. On that expedition the Russians encountered a group of Alutiiq who told them of traveling up the Copper River to trade for furs and copper (de Laguna 1972:113).

In 1797 A. A. Baranov, director of the Russian America

Company, sent Dimitri Tarkhanov to explore the Copper River and look for the

source of copper (Grinev 1993:57).

Tarkhanov reached the Lower Ahtna village of Takekat, or Hwt'aa Cae'e (Fox Creek village), located across from the

mouth of the Chitina River, and was therefore probably the first European to

see the Chitina River (Grinev 1997:8; Kari 2005). [2] But he never learned the source of the copper. In the intervening years between Tarkhanov’s

visit and the sale of Alaska to the United States in 1867, the Russians

explored parts of the Copper Basin and succeeded in establishing a small

trading post in the vicinity of Taral (Ketz 1983, Pratt 1998, VanStone 1955),

but they apparently never explored the Chitina River or located the source of

copper.

Allen (1900) may have been the first non-Native to be

shown a source of copper.[3] In April of 1885 he and his party walked up

the Chitina to visit Chief Nicolai at his house on the Nizina River (Nizii Na’) (at Dan Creek). Allen wrote that Nicolai’s house was supposed

to be in the heart of the mineral region and “by him (Chief Nicolai) we were

shown the locality of a vein (of copper) which at that season of the year,

April, was above the snow line” (1900:487).

There is some question as to why Nicolai would reveal the source of

copper to Allen when according to most Russian sources the Ahtna violently

resisted showing them (Grinev 1993, 1997). One reason maybe that Nicolai felt disposed

toward Allen because he was a “nice guy” who wanted to know what Indians knew

and wanted their help, in contrast to the Russians who were “pretty bad guys.” In any event, while Allen learned the general

location of the copper the exact location of the vein was not revealed until

1899 when a group of prospectors succeeded in obtaining a map and guide from

Nicolai (Pratt 1998:90).

The novelist/historian Ronald Simpson (2001:106-107) provides one interpretation of the situation in his novel Legacy of the Chief. As Simpson imagines it, Nikolai shows Allen the source of the copper, pointing across the Chittystone River or Tsedi Ts’ese’Na’ (copper stone creek) and as he points the whitemen turn silent…“ [i]t was as if they had found something holy.” When Allen asks Nicolai to describe the place, Nicolai waves him off sensing that “he had just done something he might later regret.” Nicolai reasons that Allen is only the leader of a small expedition, not a prospector, and he only wants to know that the source of the copper exists, or so Nicolai hoped. Of course that was not the end of it. More expeditions follow, and then in 1898/99 a flood of prospectors poured into the Copper Basin. Most were headed for the Klondike, but some stayed to prospect. In the meantime the legend of the rich copper vein grew.

In fact Nicolai and his people were facing hard times

in the fall of 1899. Simpson (2001:107) imagines

that this is because earlier in the season many of Nicolai’s young people had

taken up with the prospectors, drinking and carrying on, instead of preparing

for winter. By the fall of 1899 they had

returned to Taral but the situation is exacerbated by the presence of a commercial

fishery at the mouth of the river (begun in 1889), and hundreds of prospectors

who were hunting for game and setting fire to the country.[4] As Simpson writes, it could not have been a

better time to approach Nicolai with a proposition for learning the location of

the copper.

The facts of the situation are that Nicolai did

reveal a source of copper for a cache of supplies and for this he has been

demeaned by some as the savage innocent who “traded a multimilliondollar copper

mine for a cache of food” (Janson 1975:8; Mendenhall and Schrader 1903:28). From this perspective the Ahtna are

considered passive participants who made little contribution to the history of

the region except to reveal the source of the copper that gave the industry its

start (Pratt 1998:90). Simpson (2001:11)

imagines a smarter and more calculating Nicolai, who cannot know the value of

the copper to the outside world but realizes it must be worth something and

therefore has to wring some meaningful concessions from the white men. The prospectors suggest that they split their

cache of food with the Ahtna, but Nikolai bargains, asking for all of the food

and the prospectors’ word that they will build a clinic for the Indians. In the end the Nicolai reveals the source of

the copper, gets the food, staving off starvation, and eventually a clinic,

though it is built long after Nicolai dies. This fictional account leaves out the fact

that what Nicolai revealed to the prospectors was essentially worthless to the

Ahtna, who had no need to mine copper since they could easily pick it up off of

the ground. It was also worthless to the

mining industry. Richer copper deposits were found further west in the Kennicott

valley and the Nicolai prospect never produced any copper (Bleakley

forthcoming).[5] But overriding the argument of whether

Nicolai was duped or not is the fact that the Ahtna were never compensated by

the mining industry for the use of Ahtna lands or the minerals extracted from

those lands.

As Simpson’s Nicolai knows, the world is changing, but

little is written about how those changes affected the Ahtna. Instead historians have focused on the heroic

efforts to build the Copper River Northwestern railroad and the Kennecott mine.

Simpson’s Nicolai sees a different story. The whites have introduced disease and whisky,

“which is like a disease” (Simpson 2001:113). As a result traditional society begins to fall

apart as young people stop listening to their leaders and go off to live the

easy life and work for wages. Men become

drunk and useless and it falls to the women to take up the slack.

Eventually a syndicate of eastern financiers, that

included the Guggenheim brothers and the House of Morgan, developed the

Kennicott valley prospects and built the Copper River Northwestern Railroad to

transport the ore to tidewater (Bleakley forthcoming). Construction of the railroad began in 1907 and

was completed in 1911. The Kennecott

mine was open until 1935 and the railroad abandoned by the end of 1938. The Ahtna received practically no benefit

from the mine or the railroad although both were well within their traditional

territory.

While copper was important to

the Ahtna as a material and trade item, salmon were critical to their existence

and it was over salmon that Ahtna challenged American industry and government

A

commercial fishery began to exploit Copper River salmon runs in 1889 and by

1896 the Ahtna were protesting that the runs were depleted, and they were

facing starvation (Moser 1901: 134). In

1915 commercial fishers began fishing in the Copper River and built a cannery at

Abercrombie located about 55 miles north of Cordova. The success of this cannery attracted others,

and in 1916 and 1917 more canneries were built.

As a result the commercial salmon harvest increased from an average of

about 250,000 sockeye before 1915, to over 600,000 in 1915, and over 1.25

million in 1919 (Gilbert 1921:1).

The Ahtna protested and eventually

their complaint came to the attention of the U.S. Bureau of Education, the

agency responsible for the welfare of Native people in Alaska. Arthur Miller, an agent of the bureau working

at Copper Center, drafted a formal petition.

Miller believed the problem was not that the Ahtna were starving because

of lack of fish but that the canneries made it difficult for them to catch

enough fish using their traditional method of dip netting. Fish wheels, according to Miller, were a good

alternative but too expensive for the average Native. One of Miller’s solutions was to provide the

Ahtna with “government supervision” to teach the Ahtna how to run fish wheels to

obtain a normal supply of salmon (Lyman 1916).

Figure 14 (below) is a map made by Miller to present at a hearing about the

Copper River fishery in Seattle in November 1918. Unlike more official maps this map emphasizes

the presence of the Ahtna and was used to present their case to the government

and commercial fishing industry. The map

shows the locations of Ahtna villages and estimated populations as well as the

location of the commercial fishery in Miles Lake as well as the location of the

cannery at mile 55. The pencil marks in

Miles Lake represent commercial set nets.

Eventually commercial fishing within the Copper River was banned; saving

the fishery from probable extinction. In

the end neither the mining industry nor the commercial fishing industry provided

any benefits to the Ahtna.

|

|

6. Recreational wonderland

During world War II the road system in Alaska was

improved so that by the end of the war the Copper River and its rich salmon

resource was accessible by road from the growing urban centers of Anchorage and

Fairbanks. In effect Ahtna territory

became a recreational area for non-Natives who wanted to fish or hunt. Figure

15 is a map produced by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game showing

recreational fishing locations within the Copper Basin. Many of these locations were traditional

Ahtna fishing sites (see Figure 2).

| Figure 15. Recreational fishing in the Copper River Basin |

7. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of

1971

Between 1867 and 1958, when Alaska became a state,

the federal government did little to clarify the issue of Native land

claims. When the State of Alaska was

admitted into the Union in 1958, the new State was authorized to select and

obtain title to more than 103 million acres of public lands. These lands were regarded as essential to the

economic viability of the State. Although

the Act stipulated that Native lands were exempt from selection, the State

swiftly moved to expropriate lands clearly used and occupied by Native

villages. The Department of Interior's

Bureau of Land Management, without informing the villages affected and ignoring

the blanket claims the Natives already had on file, began to process the State

selections. Natives became alarmed and

pressed for a settlement of their claims.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971 was a

watershed in Alaska Native history. In

exchange for relinquishing their aboriginal land claims and hunting and fishing

rights, Alaska Natives received one billion dollars and 49 million acres of

land (Anderson 2007). Instead of

creating reservations the land was conveyed to Native corporations, whose

stockholders are the Native people. Shown on Figure 16 in orange are the lands

received by the Ahtna through ANCSA. The

heavy red line outlines Ahtna traditional territory. The yellow stars represent current Ahtna

villages. All the villages are located

along the road system. State land is

shown in blue federal land in green (Wrangell St. Elias National Park) and

yellow (land managed by the Bureau of Land Management.

Notes

|

|

Notes

[1] The maps in this series come from various collections: NOAA Office of Coast Survey Historical Map and Chart Collection; Geological Survey of Alabama, http://alabamamaps.us.edu; U.S. National Archives, Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

[2] According to Tarkhanov (Grinev 1997:8), the chief of

Takekat, who was named Kaltysh, and his family went in the fall to mouth the

Copper River to prepare yukola, or split dried fish and while there Takekat

probably “conducted a profitable trade in copper which his fellow tribesmen

procured on the upper reaches of the river.”

[3] There is some question as to whether the prospector

John Bremner actually explored the Chitina River (Pratt 1998:87). Bremener spent the winter of 1883/84 at Taral

and was said to have explored the Chitina River sometime between February and

April 1885 (cf. VanStone 1955:118).

[5] Thanks to Geoff Bleakley for pointing out that the Ahtna never mined copper because they could easily pick it up off the ground.